Do we need to run or drive to the store to buy another potion

so we can make our plants’ leaves look like these

maybe two or three times a year?

The answer is in the refrigerator.

Enjoy the luster for weeks to come!

Author: Flash

Dry Rot Repair

Dry rot is one of wood’s and property owner’s eternal and very costly enemies. In researching how to repair dry rot for personal use, we have come across a web site that is almost hard to believe.

http://www.abatron.com

The company sells a solution type A and type B sort of thing and has done extensive work for the U.S. government repairing thousands of windows first by neutralizing the dry rot problem and then by repairing them with their filler.

Below is an excerpt from their awesome project gallery which is a ‘must see’.

“The U.S. Department of Agriculture Building was the largest office building in the world until the erection of the Pentagon. LiquidWood® and WoodEpox® were used to restore over 8000 deteriorating windows in the South Building in 1986-1996. The most severely deteriorated windows were on the south end of the building. WoodEpox made possible the preservation of the windows on this side. LiquidWood was used on all of the window sills and 8 inches up on the frames. After restoration, the wood was primed and painted.”

For better understanding, the web site below clearly shows and explains the Abatron product in use.

http://www.hammerzone.com/archives/decks/oldporch/framing/rot_repair.htm

All in all this is a solution that depending upon the gravity of the problem, could save some sweet hard earned dollars.

A Bit Of Pasta History

Who was responsible for the origins of pasta? Was it the Chinese, the Arabs or the Italians?

Marco Polo brought to Italy Chinese noodles in 1295 but historians agree that some kind of pasta was already present in the Italian peninsula long before this date.

Etruscan tomb paintings clearly depict utensils such as pastry boards, rolling pins and wheels that are remarkably similar to today’s utensils for making pasta.

The Romans made unleavened type of dough with flour and water which they fried, cut into strips and ate with some kind of sauce.

Marcus Gavius Apicius, a famous Roman gastronome from the 1st century A.D. described dishes in which pasta dough was layered with other ingredients and then baked. This might have been an early type of lasagna.

The island of Sicily was invaded by the Arabs in the 9th century and there is ample evidence that the Arabs brought with them a dried noodle-like product.

The beauty of this dry product meant that it could be kept fresh for days to come.

There is also evidence the Sicilians were the first to boil their pasta and by the 12th century were eating a long thin type of pasta like spaghetti.

Even today many Sicilian pasta recipes still include Arab gastronomic ingredients such as raisins and spices like cinnamon.

Across from Sicily on the main land, it was the Calabrians who mastered the art of giving pasta some of the shapes we know today.

In Italian cook books of the 13th century published before the return of Marco Polo from China there are many citations of recipes for making different pasta shapes, such as ravioli, vermicelli and tortellini.

So, pasta existed in Italy before Marco Polo and the pasta museum in Rome has plenty of etchings, paintings and writings to substantiate that.

The fertile lands around Naples proved to be ideal for growing durum wheat and the combination of sun and wind made it possible to dry the pasta easily. This contributed to the beginning of the commercial pasta industry.

By the end of the 18th century the consumption of pasta in Italy sky rocketed and maccheroni, spaghetti and tagliatelle, made of flour and water, were the first ones to commercially take off.

Pasta at the time was regarded as a food for the poor.

The southern weather of Italy was not only ideal to make the pasta but to also grow tomatoes.

Pasta al pomodoro was here to stay.

Italy offers over 350 different shapes of pasta. The shapes not only inspire presentation but offer a slightly different chewing experience and taste.

Eye openers:

Christopher Columbus brought the tomato to Spain from North America and rumors widely spread through Europe of tomatoes being poisonous.

It was not until many decades after the tomato was introduced to Italy that it became one of the main ingredients in the Italian diet.

Durum wheat is probably the most important as well as hardest type of wheat grown today. It dates back to 7,000 B.C. originating from central Europe and the Near East.

Durum in Latin means “hard”.

Semolina is the purified middlings of durum wheat (grano duro) and it used to make the better and harder quality pasta.

The word semolina derives from Italian semola which in turn derives from Latin simila and which means flour. Semolina from durum wheat has widely been used in India and Turkey forever but it is known by different names.

Al Dente means “to the tooth” and refers to pasta cooked semi hard to hard. This is the preferred way to do it.

Parmigiano Reggiano originates from the northern Emilia Romagna region, more accurately from the city of Parma, and is the classic choice of cheese sprinkled over pasta.

It will taste best when grated to a medium consistency, say neither too sandy nor shredded in long strands. The purchased parmesan from Kraft is too sandy, feels gritty in the throat and absorbs the sauce too much. Other pre grated cheeses might be shredded in strands way too long unbalancing the delicate combined ratio of cheese to sauce.

For best consistency, the best way to informally sprinkle the cheese is with the fingers.

For formal situations the spoon aided by the tapping of the index finger is also an elegant classic.

Confucius would have said:

• A perfect and balanced pasta bite is the proportional ratio of cheese, pasta and sauce!

• Pasta and Parmiggiano Reggiano are one of the best marriages ever.

Altered Felt Tip Markers

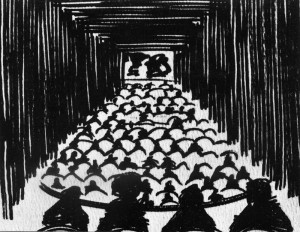

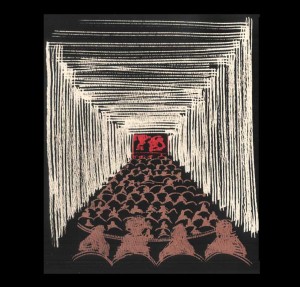

The two sketches were done with an altered felt tip marker.

By altered it is meant that three incisions through the wide felt tip and toward the barrel were made with a utility knife. This generated the look of the triple line brush stroke.

Take the amount of lines you see in parts of the sketches and divide by 3. Those are the number of strokes that produced them.

The sketches have been taken a step further:

1. Photographed and printed in black and white.

2. Developed over 8×10 negative film which means that what would have printed black on paper was actually clear on the film.

3. White and red paper, as well as copper simulated film were applied to the back of the negative film for color.

3. White and red paper, as well as copper simulated film were applied to the back of the negative film for color.

The technique allows single, multiple colors or even a texture to be used in back of the film.

If the negative film of the swamp had red paper in the back, because of the luster of the film, it would look like red ink.

Tips:

One can easily take a Flair felt tip pen and give it a chisel point either by using a utility knife or a pair of scissors.

One can also alter the felt tips in other creative ways, even getting a spongy effect when the tip is heavily butchered.

Some chisel pointed felt tip pens are available for purchase but the methods above can customize to suit needy situations and will not be found in the art supplies section.

If nothing else we could say “I did it my way”.

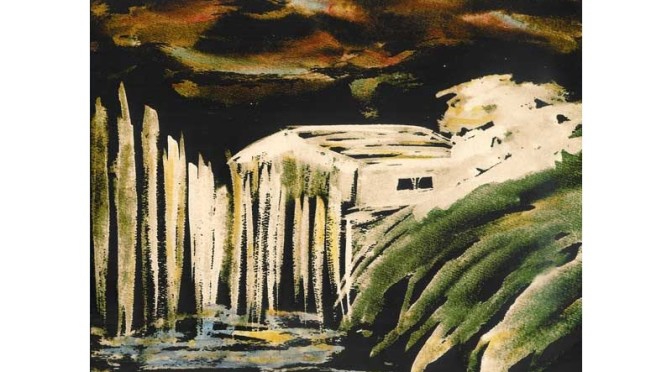

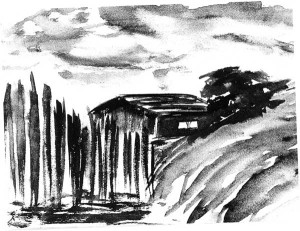

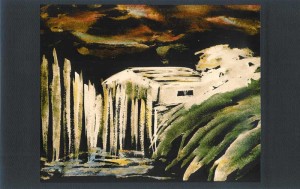

Fake Watercolor

• The original watercolor was photographed in Black/White film and printed on high contrast Black/White Agfa paper.

• From the Black/White film an 8×10 was also developed on negative film which means that what would have printed black on paper was actually clear on the film.

• From the Black/White film an 8×10 was also developed on negative film which means that what would have printed black on paper was actually clear on the film.

• Colors were added to the back of the film with felt tip markers while occasionally blending the colors with the fingers.

• The original watercolor paper texture is visible but the colors are not watercolors.

Tip:

Inserting lighter fluid in the marker, such as the Magic Marker from the old days, will extend its life for some time while at times making the color a bit lighter.